When does the history of cinema begin? It sounds like a simple question, but the answer is surprisingly slippery. We could start in December of 1895 (or was it October?), when the Lumière brothers presented what was likely the first commercial film screening. Or we could start in late 1894 (or early 1895?) when W.K.L. Dickson shot The Dickson Experimental Sound Film, creating what was likely the first film with synchronized sound. But we could also start as early as 1888 when Louis Le Prince used a single-lens camera and paper film to create the Roundhay Garden Scene, or in 1878 when Eadweard Muybridge shot his first motion studies, or even in 1874 when Jules Janssen tested if his “photographic revolver” could capture the transit of Venus across the sun.

In reality “new” technologies don’t emerge fully formed in a singular historic moment; they are always the result of numerous previous developments. The process is iterative.

It’s no different with cinema: centuries of technological innovation led, eventually, to the invention of moving pictures. Here, briefly, are a few.

Optical toys

Also known as “philosophical toys,” these objects represent some of the earliest animation technologies available.

- Magic lanterns use light shined through transparent colored material to project images onto a surface.

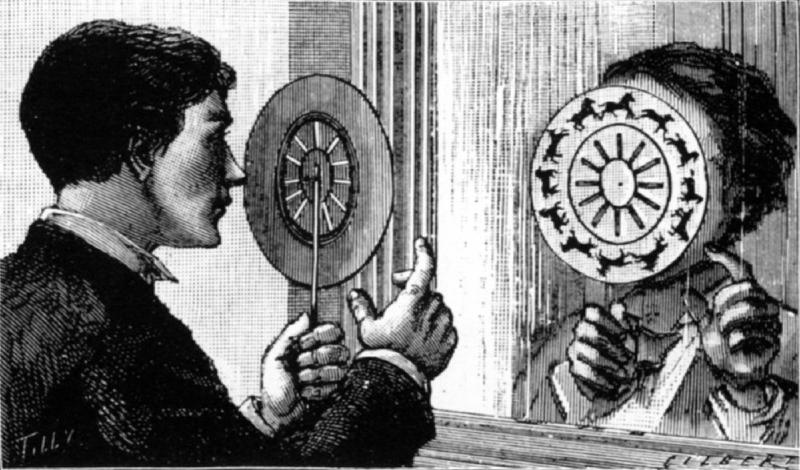

- The Phénakisticope (1832) is a disc with slits and a succession of images. When the disc is spun and the viewer looks through the slits into a mirror, the succession of images gives the appearance of a single moving image (a phenomenon known as apparent motion).

- The zoetrope (1834) operates on the same principle but removed the need for a mirror. Viewers look through slits in a rotating cylinder at images arranged around the inside.

- The Kinematoscope (1861) had viewers look through slits at images on the blades of a rotating paddle, which was operated by a hand crank.

- The praxinoscope (1877) improved on the zoetrope by using a set of mirrors to reflect the image, alleviating the need for the viewer to look through slits. This brightens the image.

- Eadweard Muybridge’s zoopraxiscope (1879) combined the principles of the magic lantern and the phénakisticope to project a succession of images from a spinning glass disc.1

I first learned about optical toys and their relationship to film from Patrick Ellis, when our paths crossed at Georgia Tech. Patrick had a collection of reproduction optical toys that he would use in his classes, and he generous lent them to me when I taught my first course where film was the primary focus. Watching students learn about early moving picture technology was so fun that, when I left GT for TCU, one of the first things I did was get a micro-grant to buy the department our own collection of zoetropes, praxinoscopes, phenikisticopes, and even some humble flipbooks.

Photography

The possibility for photography rests on two combined principles: the ability of an image to be projected via a camera obscura and the fact that certain materials change when they are exposed to light. In the early 19th century, artists and inventors worked to perfect the process of combining these principles to create photographic images.

The oldest surviving photographic image was created by Joseph Nicéphore Niépce in 1827. It shows a view of buildings and countryside, taken from a high window.

In 1838, Louis Daguerre created an image that is widely thought to be the first photograph containing people. However, the image took so long to expose that only two figures who stood still can be seen.

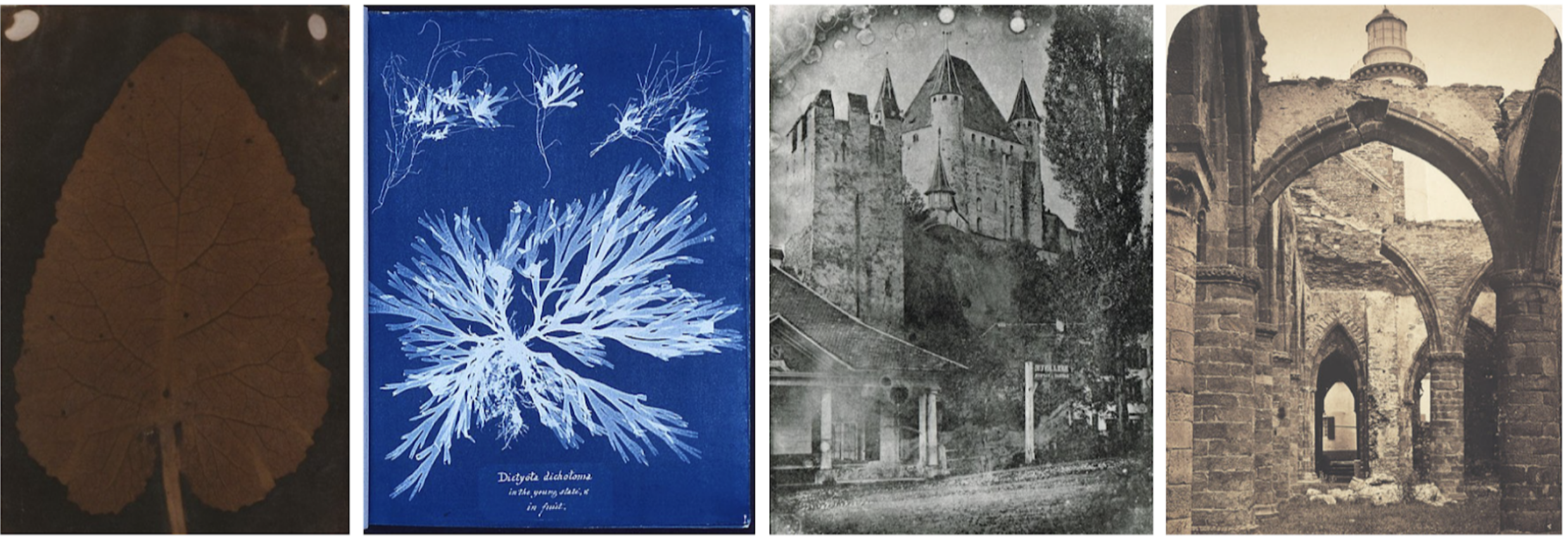

Women also experimented with photography from its earliest era. The first known photograph by a woman is an image of a leaf, taken in 1839 by Sarah Anne Bright.2 Below are some examples of early photographs taken by women.

In the United States, portrait photography became especially popular, leading to portrait studios in every city. Augustus Washington, a free person of color born in New Jersey, opened his own photography studio in Hartford, Connecticut, in 1846. He took the first photographs of his fellow abolitionist John Brown in 1846 or 1847.

In the 1870s, photographer Eadweard Muybridge was hired by Leland Stanford to photograph a horse. Muybridge spent most of the decade working out how to expose an image fast enough to capture a galloping horse.3 By 1878, with the help of some railroad engineers, Muybridge devised a way to take not just one but a sequence of photographs of a moving subject.4

Muybridge spent another 10 years photographing animals and humans in motion. He also invented the zoopraxiscope to demonstrate moving illustrations based on his photographs. Because the zoopraxiscope caused image distortion when projected, the photographs had to be recreated as illustrations that compensated for this foreshortening effect.

Meanwhile, in 1882, Étienne-Jules Marey devised a means of taking 12 photographs per second, using a mechanism that looked like a gun. He was soon able to push this up to 30 frames per second. Unlike Muybridge’s motion studies, which used separate cameras to photograph onto separate plates, Marey’s use of a single camera allowed him to expose multiple images on the same glass plate or strip of photographic paper.

In 1889, George Eastman’s photography company began selling a flexible celluloid film stock that was more durable than paper. Eastman’s company also created the first film roll system and the sprocket holes that allow film to be advanced inside the camera. This proved useful not only for still photographers, who no longer had to carry heavy glass plates, but also for budding motion picture photographers, as it brought them even closer to being able to expose the hundreds of frames need to capture more than a few seconds of motion.

Sound recording and playback

The earliest known device for recording sound, called the phonautograph, was invented in France in the 1850s. The device recorded a visual representation of soundwaves on paper or glass, but it was not originally possible to play them back.

According to Wikipedia:

Apparently, it did not occur to anyone before the 1870s that the recordings, called phonautograms, contained enough information about the sound that they could, in theory, be used to recreate it. Because the phonautogram tracing was an insubstantial two-dimensional line, direct physical playback was impossible in any case. However, several phonautograms recorded before 1861 were successfully played as sound in 2008 by optically scanning them and using a computer to process the scans into digital audio files. 5

In the 1870s and 1880s, Thomas Edison and other inventors worked out various ways to both record sound and play it back, by scratching grooves into soft materials and then retracing those grooves while amplifying the resulting vibrations.

By the late 1880s, all of the major components necessary for the invention of moving pictures were in place.

-

Eadweard Muybridge, Zoopraxographer: The Life and Work of the Photographer and Cinema Pioneer (1975, dir. by Thom Andersen). This is a great documentary to put on if you need help falling asleep. ↩︎

-

Timeline of women in photography. Wikipedia. ↩︎

-

Rebecca Solnit. River of Shadows: Eadweard Muybridge and the Technological Wild West. Viking, 2003. ↩︎

-

You might recognize this sequence of photographs from Jordan Peele’s Nope (2022). He took a bit of creative license with the history. ↩︎

-

“Phonautograph.” Wikipedia. For videos demonstrating how this was accomplished, see “Humanity’s first recording of its own voice.” First Sounds, 2014. ↩︎