One reason I love teaching film is because I vividly remember so many of the incredible people who taught it to me, along with their strategies for doing so. I have forgotten many, many other things from my life, but I still remember the playwriting teacher I had in high school who gave us the following analytical exercise: take the first and last image of any given film and demonstrate how those two images alone tell the story.

I thought of this exercise recently as I was making notes on the structure of Gold Diggers of 1933, the pre-code, backstage, Depression-era musical released by Warner Bros. and choreographed/co-directed by Busby Berkeley.

The first shot of the film is a close up on a giant coin, featuring a woman’s face in profile and the year. It’s too big and too flat to look real, and we will soon figure out that it’s a prop in the movie’s first musical number, “We’re in the Money.” What appears to be a pile of shiny coins will soon be revealed as the glittering scale armour of Ginger Rogers, who can’t even get through the whole manic opening number about the banishment of the Depression before the police arrive to repossess everything in the theatre, including the chorus girls’ costumes.

In contrast, the final shot of the film is an extreme wide that finds Joan Blondell, in character as a street sex worker, surrounded by downtrodden men and women meant to personify the suffering of the Depression-era working classes. Behind them, three arched platforms are populated by World War I soldiers in silhouette (a bleak twist on the silhoutted women who appear during the earlier song “Pettin’ in the Park”). And above that, the theatre’s curtain hangs almost out of frame, reminding us that this is the climactic finale of the show-within-a-show (or movie, in this case).

That narrative structure is interesting, I think, because at first glance the above two shots don’t really seem to tell the story at all. Our gold diggers, Polly (Ruby Keeler), Carol (Joan Blondell), and Trixie (Aline MacMahon), begin the story starving in a one room apartment, stealing milk from the neighbor and a dress from a friend (Fay, played by Rogers). But by the end of the movie they have all snagged the rich husbands of their dreams—and some of them are even in love.

So the plots of the movie and the show-within-the-movie travel in opposite directions: the movie’s romance plot starts low and ends high, while the show’s musical numbers take us from the highs of being in the money to the lows of Carol’s torch song.

Narrative in the shape of an X

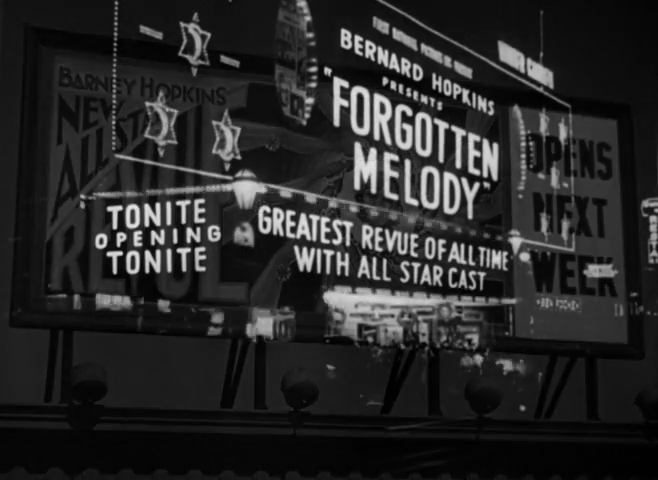

This contrapposto1 structure allows for the kind of delayed gratification Busby Berkeley seemed to love. After the cops’ rude interruption of the opening song and dance number, it’s 35 minutes until the film gives us a full musical sequence. This opening section is instead filled with snatches of songs from rehearsals and songwriting sessions, as producer and talent work together to take the “Forgotten Melody” revue from idea to reality.2

With the conclusion of “Pettin’ in the Park,” the first section of the film—the Depression-steeped struggle to put on the show—comes to an end. The revue has gone on, with secretly wealthy songwriter Brad Roberts (Dick Powell) both putting up the funding and filling in for the aging “juvenile” lead.

But the solution to the problems of the first section—how will they fund the show and who will star in it?—create the problems of the film’s second section. Brad, who was happy to put up the money but wouldn’t go onstage until Trixie tells him that if he doesn’t, the chorines will have to resort to sex work, has caused quite the society stir by appearing in the show. We soon learn that he is not a bank robber, as Trixie believes, but the wayward son of a wealthy family. His brother Lawrence (Warren William) and family lawyer Peabody (Guy Kibbee) arrive to put an end to his Broadway songwriting aspirations, but they are no match for Trixie and Carol.

As a result of the Depression, films in the first half of the 30s favored a hard-hitting, anti-establishment mood… only those antics of the monied class caricaturing them as willful, spoilt, manic and otherwise unsympathetic were accepted by moviegoers… this mood reached its climax with films like Public Enemy and Gold Diggers of 1933.

—John Kobal, Gotta Sing, Gotta Dance p. 93-4

When the plot interrupts the music

The girls take these self-important rich men for quite a ride, in the gold-digging romance plot that takes up the majority of the rest of the film. Again Berkeley and director Mervyn LeRoy delay the resumption of the musical numbers: it takes another 40 minutes and the initial resolution of the romance plot before the next Berkeley musical extravaganza, “The Shadow Waltz.”

We’re used to thinking about musical numbers as either furthering or interrupting the plot. But Gold Diggers of 1933 presents a third possibility: here it’s the plot that interrupts the music. This is made literal in the third and final section of the film, when Lawrence’s final threat to Brad and Polly’s romance prevents the “Forgotten Man” finale from starting.

The movie’s reality and the world of show biz begin to merge, as producer Barney spoils Lawrence’s plan by recognizing the “cop” he has brought in as a Broadway ham actor. With the threat revealed to be fake and all obstacles overcome, the movie and the show are free to conclude with the “Forgotten Man number” previously announced.

“Won’t you bring him back again?”

Berkeley’s big numbers, generally sung by Dick Powell, Ruby Keeler, or Joan Blondell, comprised one of the Hollywood musical’s unique styles, instantly recognizable. Even more basic to these films, however, is the characteristic Warners political reading that shapes them. Gold Diggers of 1933 is suffused with Depression panic. Performing is work; one works to eat. And, lest we forget, the film closes with “Remember My Forgotten Man,” a Berkeley phantasmagoria on the socially disinherited war veteran.

—Ethan Mordden, The Hollywood Studios p. 236

It could be folly to try to explain what Berkeley meant by any of the finales he crafted for Warner Bros.’s backstage musicals in this era. 42nd Street (1933) has Powell and Keeler waving placidly from the top of a skyscraper, a positively bland ending compared to the opium-induced Orientalist fever dream that ends Footlight Parade (1933), or Winnifred Shaw plummeting to her death during the finale of Gold Diggers of 1935 (1935).

But let’s return to the contrast between Gold Diggers of 1933’s opening and closing shots. Ginger Rogers’s Fay has previously been evicted from the film by Trixie for threatening the triple-marriage resolution that lets us reach the finale. Instead of her falsely-optimistic Pig Latin nonsense (“ear-way in-hay the oney-may”), we end with a heightened version of Warners’ characteristic social(ist) realism, a Broadway fantasy more real than the suggestion that starving showgirls can be rescued by love—or at least by easily-manipulated rich men.

At the same time, the film’s contrapposto plots are always commenting on each other. “Remember My Forgotten Man” isn’t just about the men who returned injured from World War I only to end up waiting in line for a single slice of bread during the Depression. It’s also about the women, who have even fewer options for economic stability. As Etta Moten sings, “forgetting him, you see / means you’re forgetting me.”

It’s fun to watch chiseling showgirls bilk rich men out of thousands—but it’s also a reminder of the very real, devastating consequences of the United States’ nearly non-existant social safety net. Gold Diggers of 1933 uses its narrative structure to make this point: the gold digger and the street sex worker are but two sides of the same big, flat, fake coin that opens the film.