Penetrating Looks #

When the Final Girl (in films like Hell Night, Texas Chainsaw II, and even Splatter University) assumes the ‘active investigating gaze’, she exactly reverses the look, making a spectacle of the killer and a spectator of herself.

–Carol Clover, Men, Women, and Chainsaws

Slasher films present us in startlingly direct terms with a world in which male and female are at desperate odds but in which, at the same time, masculinity and femininity are more states of mind than body.

–Carol Clover, Men, Women, and Chainsaws

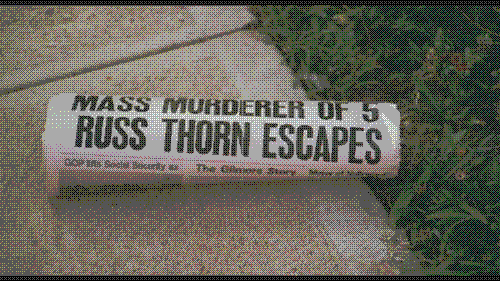

Laura Mulvey built her influential reading of the male gaze around classic Hollywood cinema, but other feminist film theorists complicated her ideas by examining other kinds of movies. Carol Clover looked to horror films, especially slashers, which had become popular in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Clover argued that because these films were formulaic, crude, and targeted at teen boys, they were a compelling place to analyze gendered representations and the complexities of the cinematic gaze. While slasher films might at first glance seem purely misogynistic, Clover urges us to read the camerawork, plot, and tropes of these films–especially the character type of the final girl–as more complicated than that.

What filmmakers seem to know better than film critics is that gender is less a wall than a permeable membrane.

–Carol Clover, Men, Women, and Chainsaws

The gender-identity game, in short, is too patterned and too pervasive in the slasher film to be dismissed… It would seem instead to be an integral element of the particular brand of bodily sensation in which the genre trades.

–Carol Clover, Men, Women, and Chainsaws

Clover pays close attention to the first-person camera work of slasher films and a later chapter of her book is dedicated entirely to eyes in horror films. Last week we watched The Hitch-hiker, in which the never-closed eye of a killer generates fear and dread in both the characters and the audience. Our theorists thus far have prompted us to think about the gaze as a kind of power. With all of this in mind, respond to one of the following prompts:

- Is the threatening gaze of the slasher film the same as the surveilling gaze of the panopticon? Why or why not?

- If the act of looking confers power on the one who looks, how can we map issues of gender onto the varied looks and gender expressions of the slasher film? Does the “gender play” that Clover describes complicate or clarify our expected ideas of the relationship between gender and power?

- Clover is very set on describing gender in binary terms (a notable weakness of 70s and 80s feminist theory). What, if any, is the relationship between the slasher film and non-binary gender identity?